Welcome to the March-April issue of FPR. We will be posting for the next several weeks, so check back for new stories. Contact the editor (see link, right) if you have a scoop!

Please scroll down for latest posts

Conservation advocates urge Congress to act on HR 1964

BY DEBORAH BOWERS

WASHINGTON, D.C. – More than 300 members of Congress agree with land conservation interests that tax deductions for charitable contributions in the form of conservation easements should become permanent – a feat that can’t be claimed by many advocates for any cause in the Nation’s capital lately, said Russell Shay, federal policy director for the Land Trust Alliance.

HR 1964 has garnered 300-plus cosponsors, a fact that supporters of the measure hope will mean the bill could come up for a vote and bring back the income tax deduction for forgone conservation easement value that ended Dec. 31, 2011. The legislation would improve upon the conservation tax deduction that had been in effect since 2006 by raising the maximum deduction a conservation donor can take from 30% of their adjusted gross income (AGI) in any year to 50%, except for qualified farmers and ranchers the deduction may be taken for up to 100% of their AGI. Also, HR 1964 would increase the period a donor can take deductions from six to 16 years.

Speaking to FPR days after Congress passed the extension of a payroll tax deduction, Shay, who is LTA’s advocate on Capitol Hill, said he was hoping to catch Congress in the mood for more of the same.

“The only way they will agree on something is to agree they wouldn’t have to pay for it,” Shay said of potential for passage of HR 1964, which doesn’t require a funding outlay but rather a forgiveness of a portion of taxable income.

“It’s my hope we will be able to persuade them to act on it this year and hopefully very quickly.” If not, Shay said the measure may linger unless Congress takes up a large scale overhaul of the tax code, which, Shay said, may not bode well for those seeking special treatment for specific transactions such as donating conservation value. Shay said he sees a Congress more apt to go in the direction of “less special treatment of special cases and a broader simpler tax code, which would leave a lot of issues on the side of the road.”

The legislation could have a substantial impact on farmland preservation programs. Conservation easements that are purchased would become eligible for the deduction under HR 1964 if sellers forgo a portion of appraised easement value, making local and state-level farmland preservation programs more attractive for those seeking tax benefits through what is called a bargain sale.

“The ability to apply a deduction against capital gains tax can make a substantial difference,” for farmland preservation or natural lands programs with limited funds, Shay said.

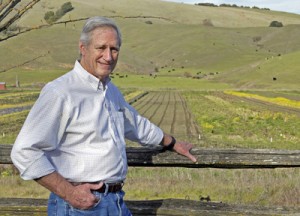

MALT director Berner to retire after 27 years

BY DEBORAH BOWERS

POINT REYES STATION, CA – Robert Berner, executive director of the Marin Agricultural Land Trust announced Feb. 11 that he will retire at the end of 2012 after 27 years of leading the nation’s first agricultural land trust. Berner was among the nation’s first farmland preservation careerists. He began during the real estate development boom years of the mid-1980s and will leave MALT at a milestone of 45,000+ acres of some of the most dramatic agricultural landscapes in America preserved for posterity.

Berner joined MALT in late 1984 and set to work developing funding sources for the purchase of conservation easements on working farms. A big break came when a statewide initiative got underway that would become Proposition 70, the Wildlife, Coastal and Park Land Conservation Act of 1988. Berner was involved in developing the initiative and helped to get it qualified for the ballot through the petitioning process.

“The overriding challenge has been and will continue to be funding,” Berner told FPR in a telephone interview following his announcement. “Since ours is a compensatory program, to sustain it we have to raise anywhere between $3 and $5 million dollars a year.” Going after grants at the local, state and federal levels is important, but MALT’s particular strength has been that half of its funding comes from individual contributions at the local level.

“That has been big, and I think that has made us more competitive.”

Berner said in a release to MALT supporters that he is “deeply grateful” for his experience at MALT and for the quality of the leadership provided by successive boards. He said MALT is “financially strong and is well-positioned to continue protecting Marin’s family farms and ranches so that they will remain a fundamental part of the county’s and the Bay Area’s unique environment, economy and quality of life.”

Marin has 255 farms and 133,275 acres of land in farms according to the 2007 U.S. Census of Agriculture. The census shows a $57.8 million annual market value of agricultural products sold. Marin is all about grazing, with cropland making up less than nine percent of the land in farms, and pasture about 82 percent. Marin’s top production is in milk and dairy products.

The hillsides above Marin’s Tomales Bay were, in the 1970s, expected to look like the city of Malibu by the 1990s. Instead, fog rolls quietly in among them, cattle can be found grazing there, and there is a sense now, even an expectation and a certainty that cattle will always graze there. That’s because of the truth behind anthropologist Margaret Mead’s advice to the world to never doubt the power of a small group of dedicated citizens to change the world. A few Marin citizens whose dedication and hard work were documented in the book Farming on the Edge by John Hart, published in 1991, met the challenge tackling the seemingly insurmountable problem of sprawl.

In the 1970s, the rule of the day was that development of farming areas, especially those near cities, as Marin is, was inevitable. The word “inevitable” caught in the throats of people who loved not only the landscape but the agricultural way of life and wanted it to survive. But the “impermanence syndrome” was hard to shake. Evidence of it was everywhere.

Not until the mid-1980s, when Californians were considering large capital outlays to pay for permanent preservation, did the specter of impermanence begin to fade. In June 1988 voters approved Proposition 70, a campaign led by the California Planning and Conservation League to address a backlog of conservation needs in the state. Prop 70 was focused on restoring and protecting wildlife, coastal and natural lands. But it was to send $15 million to coastal Marin County for farmland preservation specifically, and was the beginning of what the founders of MALT hoped was possible: to save the working landscape of agriculture and believe in the future of farming in the shadow of San Francisco.

In the early years of MALT, before anyone knew what success there would be in number of acres preserved or how much money could be raised to buy easements, it was hoped that whatever acres and farms were preserved would have a ripple effect and farms that could not be preserved would be more likely to stay in farming. But Berner believes that nothing should be left to chance.

“Certainly the more that is protected the more confident you feel, but I don’t believe we feel, and I don’t believe any of the county leadership feels that because we are now nearing 50 percent permanently protected that we don’t have to worry about the rest,” Berner told FPR in an interview following his announcement. “The forces, the dynamics that really drive our program, are still there and there’s still a critical need for what we do. I think that will continue.”

Berner said setting a goal in terms of acreage may work for some programs, and may be irrelevant for others.

“I think it depends on the circumstances in every community. In some communities it may be that once you’ve established a critical mass of farmland that the remainder is relatively secure through a combination of public policy and changes in the marketplace.” Land use practices and political leadership also figure strongly in the outcome of a farmland preservation program, Berner said. While many programs set acreage goals and attempt to define what a ‘critical mass’ of agricultural land would be within their jurisdictions, for MALT, the mission is simply to preserve as much land as possible.

“I wouldn’t say that’s necessarily the case in other areas – for example, in Sonoma County, three times larger than Marin – but for us, in a relatively small county, on the urban edge of this metropolitan area, we will continue to acquire conservation easements until we’ve done everything we can… by our calculation there are about 100,000 acres we think we may potentially acquire easements on. So, we’re at 44,000 and so that’s a rough ultimate outcome.” Berner said, however, that MALT sets no goal because it doesn’t want preservation to be about targeting. “We state it as potential, not a goal. We do imagine that in 25 or 30 years we might be fairly close to 100,000 acres. We see neither decrease in demand from landowners nor do we see any reason why we can’t continue to support, fund and carry out this program. Unless something changes we will continue.”

Berner said he expects to remain involved in MALT and in land preservation generally after departing as director, but he is also “looking forward to free time.” Berner will assist the MALT board in selecting his successor. A national search is underway.

JOB POSTING

Cherry Grove Farm, maker of artisanal cheeses, seeks general manager

Cherry Grove Farm, located in the historic district of Lawrenceville, NJ, is seeking a general manager. The farm produces and markets fine artisanal cheeses, grass-fed meats, and other farm products. The owners are committed to the principles of sustainability, environmental conservation, community engagement and excellence in our products.

The farm is uniquely situated on a heavily travelled state highway in the heart of the Philadelphia – New York Corridor, where many retail stores, restaurants and families value high-quality products from local sources. Established points of sale include an on-farm store, seasonal farm markets, year-round wholesale to restaurants and retail markets, and a growing web-based presence.

The Manager (or, couple) will be in charge of all aspects of farm management from production to marketing. He or she will be a person with demonstrated supervisory and management experience; a friendly, outgoing and inclusive manner; and creative passion for the production and marketing of local agricultural products. Appropriate backgrounds may include sustainable agricultural production, experience in food sales or distribution, or some combination of these qualifications.

Oliver, Bill and Sam Hamill, Owners ~ Please send inquiries and qualifications to Sam Hamill, smhjr@ix.netcom.com

Senate Ag Committee hears from conservation, food groups

BY DEBORAH BOWERS

Glen Chown of the Grand Traverse Regional Land Conservancy leads area tour for MI Sen. Debbie Stabenow (GTRLC photo)

WASHINGTON, DC – The Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition & Forestry’s third farm bill hearing on March 7 focused on ‘healthy food initiatives, local production and nutrition.” The topic held particular interest for committee chair Debbie Stabnow, Democrat of Michigan, where underserved neighborhoods in Detroit are the definition of food deserts that new federal farm bill policies seek to remedy. Getting fresh and wholesome foods into inner city, crime plagued neighborhoods is a challenge that has only begun to be tackled through policies and programs enacted in the last farm bill in 2007.The other side of the coin is boosting production of local foods in the state.

“In Michigan we know that if every household spent just $10 spent on locally-grown food, we could put $40 million back into the economy. When we buy local, we support local jobs. The growing demand for local food has also created great opportunities for young and beginning farmers,” Sen. Stabenow said.

Stabenow said the federal initiative, Healthy Food Financing, is aimed at bridging the gap, and have helped new wholesome food-focused grocers get established in cities such as Philadelphia and Detroit. “These stores are making profits, meeting an important need in local communities, and using food hubs to connect with local farmers,” Stabenow said in her opening statement.

A year ago, First Lady Michelle Obama, along with Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner and Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, announced in Philadelphia details of the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, which allocated more than $400 million to create incentives and to facilitate the siting of new whole-food focused grocery outlets in underserved urban and rural communities nationwide. The initiative is a partnership between the departments of Treasury, Agriculture and Health & Human Services.

“The continued success of the agricultural economy and the continued growth of jobs in agriculture require both traditional production and local efforts,” Stabenow said in her opening statement at the hearing March 7. “America’s farmers aren’t just feeding the world; they’re also feeding their neighbors and their local community. Local food efforts are leveraging private dollars to create more economic opportunity in rural communities and more choices for consumers.”

At the hearing, Arkansas produce farmer Jody Hardin told the committee how the Farmers Market Promotion Program, a 2007 farm bill grant program, built a new food system in central Arkansas.

“In total, we went from $300,000 in sales in our 2008 season to $1.5 million in our 2010 season, the year after our FMPP grant,” Hardin told Stabenow’s committee. “We quadrupled our annual sales thanks to FMPP. As farmers got wind of the increasing consumer demand, we went from between 12 and 15 farmers per market day to over 30; in other words, we doubled our farmer presence at the market in a three-year period. Through community collaboration, we developed 20 lasting partnerships with local and regional chefs that continue today. All in all, we were able to build a larger clientele, we were able to build a larger base of farmers, and we generated dollars back into the economy.”

Conservation title focus of earlier farm bill hearing

A coalition of agricultural land trusts operating in Western states and other land trusts were among those testifying on the importance of the farm bill’s Conservation Title Feb. 28. The Partnership of Rangeland Trusts, which includes the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust and the California Rangeland Trust and five others from Texas, Oregon, Wyoming, Montana and Kansas, urged the committee to “maintain conservation funding that meets our national needs by keeping our working lands in agriculture and available to wildlife and the rural communities which depend on them.” The group stated it expects conservation programs to take their share of budget cuts, but that it hoped “the Conservation Title can continue to meet vital national needs while sharing in budget reductions.”

Glen Chown, executive director of the Grand Traverse Regional Land Conservancy, told the committee that conservation organizations that worked on creating a farm bill platform last Fall, including the Land Trust Alliance and American Farmland Trust, are recommending consolidating federal working lands easement programs, such as the Farm and Ranchlands Protection Program and the Grassland Reserve Program, into a combined program that would be funded at a minimum $1 billion. The recommendation was a suggestion for trimming that is anticipated in the farm bill.

“We are aware of the deficit reduction goals of Congress and are willing partners in an effort to streamline the “alphabet soup” of programs in a manner that achieves cost savings while creating program efficiencies,” Chown said in his testimony.

Of the 260 easements held by Chown’s group, about 60 are agricultural conservation easements protecting 1,600 acres of farmland. About 7,500 acres of farmland in the Grand Traverse region is protected through township and county efforts, Chown said. Those include Acme and Peninsula Townships and the Leelanau Conservancy.

AFT study cites need for action in Puget Sound region

BY DEBORAH BOWERS

SEATTLE, WA – A study by the American Farmland Trust released in January calls upon Puget Sound counties to examine their zoning ordinances with the objective of giving farmland preservation efforts a fighting chance to succeed. The study examined and ranked the counties according to agricultural zoning effectiveness, purchase of development rights achievement, tax relief given agricultural properties, and economic development initiatives.

The study reports that in four counties development pressure has overwhelmed farmland protection efforts. Pierce, King, Snohomish and Whatcom Counties each lost more than 100,000 acres since 1950. In the entire region of 12 counties, where more than 600,000 acres are in farm use, just 30,000 acres of farmland have been placed under conservation easement.

“The foremost problem is ineffective agricultural zoning,” the study states. “While a few counties have done well with agricultural zoning, most allow significant loopholes in their regulations,” including “intermingling of farmland and rural estates,” allowing a variety of non-farm uses in ag zones and minimum lot size regulations that have significantly fragmented farm areas. In addition, much land in agricultural use is not included in ag zone designations.

Washington state-level farmland preservation funding has been insignificant compared to most other state farmland preservation programs and progress in preserved acreage has been up to the county governments.

The study provides recommendations to counties on how to strengthen farmland preservation efforts. First up, is how to amend or rewrite zoning ordinances to include all viable farm parcels in agricultural zones, decrease the number of non-agricultural uses allowed and to increase the minimum lot size, the type of zoning used in the region, to at least 40 acres, the largest in the region currently.

The study reports that farmland conversion in the region has slowed, but urges counties to make progress in purchase of development rights. Washington has enabled counties to levy certain taxes to pay for land preservation, including the Conservation Futures Tax, which allows a county to levy up to 6.25 cents per $1000 of assessed value and use all the funds for conservation easements and open space fee acquisition. While most Puget Sound counties have enacted the tax, only Skagit County uses all its revenues to fund preservation of agricultural land.

King County had a sunset PDR program that preserved 13,500 acres mostly in the 1980s, but now the county focuses on protecting greenspace around its towns using a transfer of developments (TDR) program, to date preserving 141,500 acres of what the county plan calls rural/resource land. But the AFT study cites Thurston County’s TDR program as being the most successful for farmland preservation, but it has preserved just 200 acres using TDR.

The study cites Skagit County, famous for its tulip bulb and seed production, as the most active purchase of development rights program in the region, with 7,800 total preserved acres, and its last five-year tally at 2,800 acres, an annual or semi-annual tally for some counties in the East.

The study recommends that Skagit County target farm parcels around the county’s urban borders “to ensure that farmland abutting urban centers does not convert to rural residential developments” and generally focus on lands most vulnerable to development. The study also recommends an ombudsman position be created as a liaison to the ag community to develop ag economic development and provide regulatory assistance, a recommendation that has been made in the past.